What are you looking at?

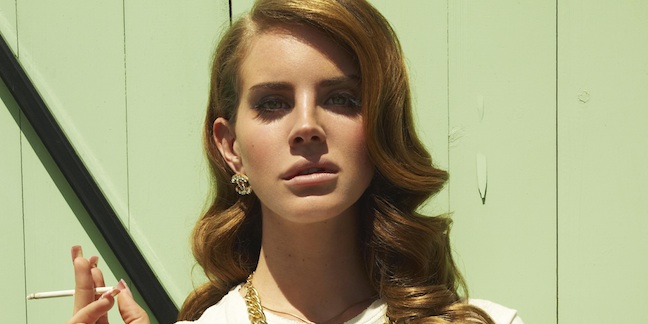

Lana Del Rey is probably a familiar name and face to you, if you waste your spare time scanning pop culture and music blogs. She has an EP out (I think?) and is releasing a full-length album at the end of January; she also performed on SNL last weekend and has been getting a ton of media attention, much of which has been negative (even angrily so). The elite, pace-setting members of the indie music scene have come down especially hard on Ms. Del Rey (a stage name), and while I can't speak to the musical criticisms qua musical criticisms, I do find the extra-musical complaints fairly compelling and accessible, because they are not very technical, and very human.

The thing is, 25-year-old Del Rey got her industry sea legs performing under her real name, Lizzy Grant, and when I say industry sea legs, I mean she stumbled between venues for a few years without gaining any real traction with the people who mattered. As competent but somewhat generic musicians are wont to do, she handily evaded commercial success.

But then Lizzy became Lana, and consequently went from being pretty in a cornfield blonde, wholesome, small-town-girl-next-door sort of way to being, well, something else. A collagen-puffed pout sealed her revamped market-ready image, which combines lapsed (and mourned) innocence with a caricaturish femme-fatale vibe and a lot of other things that make me feel weird when I watch her performing or giving interviews.

The Artist as Lizzy Grant, crowned Miss Iowa in another life

Music bloggers take real offense, it seems, because she is so clearly sculpted to appeal to denizens of their empire, the pop-indie scene. Her self-aware affectations imply a sort of wink-wink nod to something being parodied, or at least communicate the sort of po-mo playfulness that artists use to give listeners a sense of being in on something together, little cultural co-conspirators that we are. Her videos swing between whimsical and overblown images (Del Rey ensconced in a throne in what appears to be a cathedral, with tigers laying down on either side within arm's reach; Del Rey, bloodied, held in the arms of a muscular tattoo-covered dude with gauged ears, in front of the burning wreckage of their car—I don't see how you could interpret these as anything but self-aware, jokey excesses) and grainy Super 8 "found footage" style montages that evoke powerful nostalgia—even for the mid-2000s, apparently, judging from the inclusion (has to be another wink-wink moment, right?) of a familiar iPod billboard advertisement, nestled between shots of unhelmeted couples riding classic Victory motorcycles.

Even though I haven't the slightest critical chops to justify my saying anything about her music, I will say this: her tracks are, unsurprisingly, perfectly matched to the aesthetics of her persona and brand. The songs I've listened to cultivate a (self-consciously?) retro sensibility, with static-crackling samples of decades-old recordings, kitschy string intros, and moody lyrics that Del Rey delivers with a trademark croon. You may imagine it accurately with the aid of her promotional taglines, which she's apparently used to describe herself during interviews: "a gangster Nancy Sinatra," "Lolita got lost in the hood." As one online commentator points out, these sound a lot more like phrases that were tossed around in a corporate boardroom during a brainstorming session than anything a musician would say about herself off the cuff.

"Ha-ha! Americana, am I right?"

The thing is, though, all of this brand genealogy stuff seems pretty weak, insofar as it's intended as criticism. Successful musicians (perhaps with the exception of those who work exclusively in the studio) are necessarily successful performers—not only of their music, but of themselves—and creating a persona or brand is one way, perhaps the only way, of approaching performance: come up with a character to play, a simple and consumable identity that you can separate from yourself and offer as a commodity to potential listeners, fans, EP purchasers. Bring out a single theme that people can latch on to and associate with you; find an unexplored niche in the pop-cultural landscape and put your stake in the ground. It's one method among many for creating a splash, and I would go so far as to say that it's basically unrelated to the actual quality of the creative product.

But still, some artists leave us with a sense of having gone about this process of cultivating showmanship in a more "authentic" way; their onstage or video versions of themselves seem roughly natural extensions of the personalities we imagine them to exude around their families or their pets. Why does Lana Del Rey still leave such a bad taste in the mouths of so many? Do people really believe themselves to have such psychological insight and moral sensitivity in their assessments of the Del Rey persona's "truthfulness?" Is it just that people think she's a big phony, or could it have a little more to do with in-house resentment? Could it be the attention she's been receiving that other artists and a lot of critics feel is undeserved, based on her questionable talent and minuscule CV and blatant posturing?

Perhaps. But the market is obviously, always, and inherently unfair, and popular success is a cruel mistress to those who would try to court her. Del Rey set out to achieve something that she seems to have achieved, even if it's been a tough slog through bad performances and frequently caustic press that may have required her to give up something of herself. The brand she has constructed is essential to that success, and to call it what it is—manufactured—is to miss the point.

Ah yes, the point. The reason my brain keeps straining to make sense of Lana Del Rey is that frustratingly complicated aspect of her schtick that I mentioned earlier. The arch persona and intimations of irony do lead me to look for the joke, or the parody, or whatever it is that she's doing; I'm having a magnificently hard time trying to figure out the proper locus of criticism, the guiding intention that would establish a context in which her whole act might be evaluated, according to its own goals. I want to "get" the point, and am not content to believe that it's just to generate buzz.

Is it necessary for her to have the sort of determinate aim that I'm trying to uncover? Probably not, and maybe this reveals a weakness of my own in trying to understand music and musicians generally—an inability to be satisfied with a decidedly equivocal play of symbols designed to hazily evoke rather than communicate. Call it a preference; I have a greater appreciation for art that seems to ride a discernible (and criticizable) intention—for lyrics that tell stories, for instance—than art that forces its consumers to cast out feelers for shreds of meaning in purposefully jumbled and even inchoate sets of ideas and images.

Obviously there's a spectrum here, and I don't mean to be reductive, but man do I get annoyed with music and literature that isn't just obscure or difficult, but intentionally, a-priori meaningless in a cynical sort of way. Meet me halfway, creators; I love interpreting in the face of ambiguity and all its attendant tensions, and I find it bracing to bear up under the onslaught of tricks that subvert traditional artistic forms. But I hate finding out that I'm trying to make sense of something that was never meant to be more than packaged gibberish, a glossed-up sneer. Such stuff does exist, and it's angering.

Back to Del Rey. I have my theories. With the lips and the distant look, is she some sort of embodied critique of porny male sexual desire - a sendup of the appearance and attitude of a jaded longtime member of the adult film community, where the obvious artificiality implicates the viewer, as though to ask "is this what you want? A fleshed-out Barbie doll?" This could be the calculated side of a coin that flips to reveal the full-throated rage that characterized the Blood Brothers.

Or, with the grainy montage in "Video Games," is she a sad messenger angel from the past—a 60s flight attendant, somehow simultaneously from the 80s—who contrasts Morning in America in all its apparent sun-shiny resplendence with the grimness of present economic instability? Or, does the same angel sing over this montage only to show the fickleness of nostalgia and the impossibility of remembering rightly, who means to tell us that our idea of the past is a lie?

horsewoman of the apocalypse

The pictured album cover weaves together the visual tropes intended to qualify Del Rey in the public imagination. The stark center-framing, combined with her blank look, 50s housewifey hairstyle, and closed collar, evokes all the creepiness of The Stepford Wives, the freaky suburban thriller/horror film that (SPOILER ALERT) climaxes with the protagonist making a terrifying discovery just before being implicitly murdered. What does she find out? That the women in her town are being systematically killed and replaced with robotic surrogates, chillingly cheery automatons that are perfect in the eyes of the town's male inhabitants—square-jawed breadwinners who would each, of course, like nothing more than to own a beautiful woman who doesn't talk back, puts out on demand, and has none of her own needs.

The movie and the novel it's based on are satirical and intended to call out a sexist culture by hyperbolizing its inner logic of oppression. Does Del Rey present herself with a similar goal in mind? This is related to the first interpretation offered above, that of Del Rey as embodied critique of male heterosexual erotic fantasy. She could even be implicating a whole listless generation for its sins, if we take into account her song "Video Games," which laments a relationship that falters and fails because of a dude's inability to pull himself away from the wispy pleasures of his console.

This is the most charitable reading of the mythos that is possible, I figure, and unfortunately, at the end of the day, it just doesn't seem to square up with the data. Del Rey is a meticulously refined product, designed to appeal to a certain audience, and any positive or productive take on her act seems superfluous to an essentially commercial core. Here's the insidious part though, given what I've just said: Lana Del Rey totally does meet you halfway, but not in any of the myriad constructive ways that serious art does.

Here's what I mean. Lana Del Rey's intimations of irony and hidden, subversive meanings allow the listener to feel as though they're in on the joke—but one isn't being made. She ultimately seems to proffer one more version of the aforementioned postmodern playfulness that rewards quirky and whimsical musical acts with throngs of listeners. Rather than upholding an underlying, morally-superior reality, which gives irony its substance and its teeth as a tool for critique, Del Rey settles for aping the form without committing to a specified content. It's a well-trod path that recommends itself to creatives of all kinds who are trying to make a way for themselves in the lingering shadow of the fading "hipster" monolith. The result is the perpetuation of our on-hand cultural ideals of self-awareness and savvy detachment, but without positing a good worth pursuing within the aesthetic and spiritual context those ideals help to establish.

One could take this even further, however. There is one way of understanding the anti-teleological posturing of Del Rey that ascribes to her a serious and deep artistic purpose, one that transcends and even subverts the designs of the executives who first came up with her name. Unfortunately for Lizzy Grant, it's a soul-threatening move: what if Lana Del Rey is a true metaphysical nihilist?

If we take her pinched face and impossibly distant stare to a super-meta level, we might find an artist committed to showing everything to be a big fake mess. Not just fame, or commercial sexuality, or image-obsession, or a cynical music industry, but everything. Do the tigers in the deserted cathedral of the "Born to Die" video guard a faux-Nietzschean queen, crowned with relevance and wealth, offering herself as a stand-in for the sacred we no longer believe in—even dying as a martyr for this vision, her bloodstained figure a symbol of the ultimate sacrifice of oneself to one's pleasures, claiming for herself a pop-religion of smirking, tired, uncontested hedonism? We could be in on the joke after all, if the joke turns out to be the universe of human meaning.

Could Lana Del Rey be so post-ironic as to actually intend her album title as an open question: is there something else to life, or are we really born to die? Could this question be the proper locus of criticism, the interrogation of value itself the ultimate goal? If so, could we perceive in Lana Del Rey a consummate creative force—an artist with the spiritual depth to stare deeply into the abyss, whose impassive gaze back at us reveals flickers of her grappling with that overwhelming darkness, which would threaten us all?

How, then, is Lana del Rey's work different from the artists you mentioned early on who produce works that are willfully and sneeringly incoherent? Merely in that her works offer decodable criticisms but yet don't point to a superior moral plane?

ReplyDeleteAlso, I'd be interested to talk more about your desire for art to have discernible and criticizable intention. I could imagine asking, "What's the point of Beethoven's 9th?" and getting the answer, "Pretty much the point is Romanticism." Then if I can find something to criticize in Romanticism, Beethoven's 9th is culpable, too. That was actually one of the troubling questions that led me through John Cage out of music and into philosophy: If it's true that the work depends on an ideological framework for its merit, how can I find a worthy ideological framework? There's more to say about it, but I definitely need to get back to studying. Anyway, great post, dude. Keep getting rubbed-off-on by JJS.

Dan,

ReplyDeleteThank you for your invaluably astute questions; I figured you'd be the one to prod the weaker points of my analysis. I'll start with the second cluster of questions.

You're right that demanding a "point" would be too much in most cases, with classical music being a perfect example. However, there's a reason Beethoven's 9th is esteemed in the way it is, and I think any critic worth her salt would be able to articulate good reasons for its being considered a masterpiece beyond "it makes you feel awesome." A "discernible and criticizable intention" can be purely aesthetic; Romanticism provides the context and conventions within which Beethoven creates, the limitations of which he pushes against. I imagine that other composers working in the same period may be judged deficient in one way or another against his standard, for how fully he realizes the possibilities inherent in the movement of which he was a part.

Criticizing Romanticism itself would be a step beyond criticizing Beethoven according to its conventions, and somewhat near my stated preference for art produced in one spirit rather than another. There may be perfectly sound reasons for that sort of meta-judgment that exceed (and perhaps even justify!) bald statements of preference, but I think there's a different kind of criticism that sidles right up to what the artist is doing and can even help them to course-correct, and that this kind of criticism necessarily attempts to understand what the artist is aiming for—like a violin teacher trying to coax good form out of her students. I think this is a reasonable goal for at least one sort of criticism, and I think there's a version of it that it does not require a commitment to some sort of simultaneously ideal and exegete-able authorial intention in order to make sense. But we can save the hermeneutics for another time.

The reason my criticisms took more of a moral or ideological tone with Del Rey is her use of irony, for reasons I briefly sketched above. When I perceive that a meaning is being called into question, my response is to search for positive thrust, the meaning that would supplant the one being criticized. I suppose this is why I feel compelled to look for a "point" with her, when I wouldn't with other artists whose goals are more technical or purely aesthetic, even in a wordy medium.

I guess the thing I rail against is irony being entirely reduced to an aesthetic choice, as seems to be the case with Del Rey. It perpetuates the cultural tyranny that your man DFW calls out in one of the quotations I put up a few months ago. I don't appreciate an artist's using hints of social critique with a wholly commercial goal, adorning themselves with subversive symbols that they drain of symbolic power. It's depressingly cynical.

And to return to your first cluster of questions, in the end, I suppose I can't come up with solid reasons for believing that she offers much more than an airbrushed sneer. However, on my last reading—Lana Del Rey as nihilistic siren of the apocalypse—perhaps I could suggest a difference analogous to the one between the soft-headed freshman who glibly ends conversations by saying "well, I mean, it's all meaningless or whatever, anyway," and Schopenhauer himself? The difference would be on that sort of spectrum, at least, even if the degree is drastically different.

Thanks again for your questions! I hope I was able to get at what you were asking. I deeply appreciate the compliment of your close reading.