I'm frustrated with a series of short cultural analyses I've read today. It all starts with an essay by William Deresiewicz entitled "Upper Middle Brow," in which the author attempts to identify a strand of culture-production designed to "make consciousness safe for the upper middle class" by "approving our feelings and reinforcing our prejudices." A step above "midcult" (a term I hate and thought had fallen out of fashion), "upper middle brow" consists of cultural products that possess "excellence, intelligence, and integrity," but that "always let us off the hook" by failing to disrupt our assumptions and challenge us. The "us" in question refers to a nearly-new creative class of college- and postgraduate-educated professionals whose tastes verge on the downright literary.

Who is implicated in this sophisticated, stylish, post-ironic pat-on-the-back party? Apparently: Jonathan Lethem, The New Yorker, Wes Anderson, This American Life, Lost in Translation, and GIRLS. Also, "the films that should have won the Oscars." But not all of them—a handy list of midcult artifacts ("peddling uplift in the guise of big ideas") includes Malick's Tree of Life. Who else is on the midcult list? Franzen, Jonathan Safran-Foer, Middlesex. (Just separating Lethem from this company seems a microscopically fine exercise in hairsplitting, and attenuates the explanatory power of the typology.)

So what does Deresiewicz suggest as an antidote? Upper middle brow is, after all, a problem framed in a way that implies a particular solution. The suggestion he offers is that we need a return to an art that will "disturb [our] self-delight", because we are "engorged on our own virtue" and allowed, by our choices of aesthetic consumption, to remain complacent and untroubled.

Monday, November 12, 2012

Friday, November 2, 2012

Hyperbole, in Good Faith

A friend of mine used to accuse me of falling into hyperbole when describing items of interest in my life. “No,” I swore, “I don’t mean to exaggerate, I’m giving you a true record of my experience—it was truly, superlatively [adjective]!” This little essay is an attempt to get at possible motivations for spending big words on little things, while also offering a hesitant typology.

Labels:

Annie Dillard,

Anxiety,

Art,

Awareness,

Faith,

Hyperbole,

Irony,

Language,

Life,

Permanence,

Thought,

Transcendence,

Wonder

Thursday, October 25, 2012

American Life, Redux

I am back—both in the States and on the blog. Seeing as I'm unemployed, I intend to return to semi-regular postings for supercurriculum. I hope you find it worthwhile!

The new apartment address—in case of parcels, visits, or otherwise—is:

Martyn Jones

2707 N. Kedzie Ave.

Unit 2

Chicago, IL 60647

USA

Thanks for reading, everyone. You're the greatest.

The new apartment address—in case of parcels, visits, or otherwise—is:

Martyn Jones

2707 N. Kedzie Ave.

Unit 2

Chicago, IL 60647

USA

Thanks for reading, everyone. You're the greatest.

Steaks on a Plane

"Excuse me, sir, could I please see your boarding pass?"

I looked up from my laptop, instinctively tightening my feet around my bag and placing a hand on my rollaway. A woman in my airline's uniform with disarmingly large Persian eyes stood waiting for my response.

"Um, yeah sure, just a sec."

I handed it to her out of my shirt pocket, and waited to be told that I would need to go back to American Customs Pre-Clearance to sort out the ambiguities I'd inadvertently penned into my information card.

She eyed my ticket. "Please bear with me for a moment, sir." Then she walked away. I closed my computer, watched the desk under the sign for GATE 105, and thought about what a great story I'd have if I were detained in Dublin for the whole weekend by customs agents perplexed by my inconsistent passport use on flights to and from the US.

I ended up with a different story, however. My flight attendant returned and looked at me with her huge eyes. "Sorry about the confusion, sir. You'd gotten an upgrade and we wanted to make sure it was printed on your ticket." She handed me my boarding pass and I looked at it, then back up at her. "Wait a second—I'm sorry, what does this mean?" I must have misunderstood the word printed in place of "Economy" in the lower right corner, next to the almost-certainly misprinted "SEAT 3G". She replied, "It means you are now flying business class." She turned on her heel and walked away. I smiled, caught myself, furrowed my brow, and smiled again, unable to bury my excitement.

So it begins: the story of a wide-eyed midwestern boy's adventure behind the business class curtain.

Labels:

Airline,

Awareness,

Blessing,

Business Class,

Chicago,

Dublin,

First Class,

Flight,

Growing Up,

Homecoming,

Indulgence.,

Joy,

Life,

Luck,

Money,

No Money,

Transcendence,

Upgrade,

Wonder

Saturday, June 9, 2012

The Really Real and the Really, Truly, Indubitably Real

I went for a run today in the rain. By the time I got back to my building the sun had come out. With my contacts in, I was able to see a lot of detail in things that would otherwise be obscured by my glasses. I don't know if crumbled concrete and a rotting white door are proper objects of wonder, but here we are.

I was cooling down, walking and stretching, when my mind quietly seized. In the clouds and trees, even in the brick buildings and cobblestone parking lots, I saw a desert open up. Everything was a flat, consistent plane, each surface equally opaque and continuous with every other. There was a kind of inscrutable hiddenness in everything.

In this state I prayed. I asked God for a sign that this was his work. By the end of my silent prayer, everything had become a surface—not just the sights of things, but their sounds, smells, feels. My mind became a point suspended in something I know not what. I turned around like a baby in utero, looking at a world made strange.

I don't know if God answered my prayer in a way I could understand, but my heightened sense of alienation at least reopened a window that's been shut for a long time. Here's the view, familiar enough: my little brain does its best to dance over the surfaces of things, and is satisfied with a cursory knowledge of the contours they present to me. It cannot, however, open a door into a stone, or touch the life that animates an olive tree. My brain can only gesture at reality at a slant, and ponder it from a distance. Perhaps otherwise it would be consumed—or simply fall silent, like the collapsing body of the man who tried to steady the ark with his bare hand.

Maybe it really is true, that everything we think or say is essentially and most truly about what we cannot think and can never say. Who could know? And could she say it if she did know?

I was cooling down, walking and stretching, when my mind quietly seized. In the clouds and trees, even in the brick buildings and cobblestone parking lots, I saw a desert open up. Everything was a flat, consistent plane, each surface equally opaque and continuous with every other. There was a kind of inscrutable hiddenness in everything.

In this state I prayed. I asked God for a sign that this was his work. By the end of my silent prayer, everything had become a surface—not just the sights of things, but their sounds, smells, feels. My mind became a point suspended in something I know not what. I turned around like a baby in utero, looking at a world made strange.

I don't know if God answered my prayer in a way I could understand, but my heightened sense of alienation at least reopened a window that's been shut for a long time. Here's the view, familiar enough: my little brain does its best to dance over the surfaces of things, and is satisfied with a cursory knowledge of the contours they present to me. It cannot, however, open a door into a stone, or touch the life that animates an olive tree. My brain can only gesture at reality at a slant, and ponder it from a distance. Perhaps otherwise it would be consumed—or simply fall silent, like the collapsing body of the man who tried to steady the ark with his bare hand.

Maybe it really is true, that everything we think or say is essentially and most truly about what we cannot think and can never say. Who could know? And could she say it if she did know?

Saturday, June 2, 2012

Opa Leijs, 1924-2012

Yesterday I helped to lay my grandfather into the ground. We led the narrow pine casket over a gravel pathway, following a towering man in a waistcoat who gave us instructions in clear, formal diction at each stage of the procession to the plot where Opa was to be interred. After arriving there, we hoisted the coffin off its wheeled platform and placed it on a pair of steel wires that stretched over the grave. An attendant in a black suit pulled a long tool out of a hedge and pressed its end into the ground above the plot. The coffin descended, rocking gently on its cables. There was silence except for the wind and the whirr of the unseen lowering mechanism. Each family paid its respects and walked with crunching steps back to the main building.

Sunday, May 20, 2012

Crucible

Radio silence until June 1. The thesis and three papers are all due on May 29. May God have mercy on our souls.

the promise of June

Wednesday, May 9, 2012

One More Night in Leuven

In the afternoon, a surprise storm blasts Leuven with bizarrely-intense rainfall. I hear a rumble grow in our apartment and assume that a pot is coming to a boil on the stove. A sideways glance reveals roommate Dan in mid-reaction to something outside. I stand and look: water from the sky is roaring on the glass. The pot in the kitchen is drying on the rack.

I walk to an unlatched window that has blown open and the force of the storm astonishes me; I haven’t seen rain like this for a long time. Agitated and smiling, I superfluously yell down to a drenched bro running in the courtyard “run, bro!”, and this earns me a middle finger. The bro and I both laugh. He probably didn’t understand me. Twenty minutes later, a rainbow arcs out to the south; it looks as though it was painted on a photograph. Before I can take a second picture with Dan’s camera the color fades into the sky. My soul throws Dan's camera out the window in frustration before my physical hands return it to him.

Labels:

Apartment,

Belgian Life,

Camera,

Contentment,

Hope,

Leuven,

PROCRASTINATION POST

Location:

Leuven, Belgium

Wednesday, April 18, 2012

Sci-Fi Thought Experiment

A kind of hominid on a planet like ours has evolved with a head that is tilted at a 90º angle, so that the chin of the skull fuses with the top of the chest; the survival of the species is miraculous and a result of an astoundingly high mean intelligence. Forward motion induces vertigo for these creatures' being unable to set their eyes on a point in the middle distance, as we do; they survived for ages in sheer cliff dwellings, are excellent climbers, and have developed a civilization that ingeniously accommodates their apparent biological deformity. Unable to look up at the sky or out at their larger surroundings without great difficulty, they have constructed enormous cities with tiny architectural footprints; these towers are built to resemble the cliffs that sheltered the species in the early days of its history.

To compensate with technology for the cruel genetic hand that nature somehow dealt them, these creatures have devised a video monitor system that affixes to their clothing with a special apparatus; it displays an image directly under the earth-pointed face of its wearer. The image is of the area directly in front of the creature, and so mimics what we understand to be normal human sight. Rapid forward motion, however—whether from running or piloting a vehicle—is experienced as psychically akin to falling, because falling is the only visual analogue available to them for it. Genetic memory therefore makes long-distance travel terrifying, and the new technology has inspired a genre of fiction that mythologizes horizontal motion, and plumbs the psychological depths of the minds of those so unfortunate as to undergo it. In these works, which are intelligible to us as poetry, a full-speed run may tear a rip in the fabric of reality, and pilots spontaneously catch fire, and walking around on the ground outside a village may cause it to collapse into a sudden abyss. Speed as such is a cultural wellspring of dread and provides a context in which daring and fear alike are made manifest.

To compensate with technology for the cruel genetic hand that nature somehow dealt them, these creatures have devised a video monitor system that affixes to their clothing with a special apparatus; it displays an image directly under the earth-pointed face of its wearer. The image is of the area directly in front of the creature, and so mimics what we understand to be normal human sight. Rapid forward motion, however—whether from running or piloting a vehicle—is experienced as psychically akin to falling, because falling is the only visual analogue available to them for it. Genetic memory therefore makes long-distance travel terrifying, and the new technology has inspired a genre of fiction that mythologizes horizontal motion, and plumbs the psychological depths of the minds of those so unfortunate as to undergo it. In these works, which are intelligible to us as poetry, a full-speed run may tear a rip in the fabric of reality, and pilots spontaneously catch fire, and walking around on the ground outside a village may cause it to collapse into a sudden abyss. Speed as such is a cultural wellspring of dread and provides a context in which daring and fear alike are made manifest.

Tuesday, April 10, 2012

East Berlin

My sister's apartment is two blocks from where the wall once stood. To memorialize it, they've put up a long row of steel framing poles that replicates its original interior scaffolding. The architectural differences between the city's two halves remain, in spite of almost a quarter-century's worth of colorful renovations on both sides. My sister is taking the day off work tomorrow in order to show us around. I look forward to expanding my acquaintance with Berlin beyond the insides of a couple of apartments and trams.

To get here we rode a long-distance train—no private compartment for us, though; in a show of solidarity we opted for "proletariat class" seating, and were even blessed with access to the bar car for our good-faith gesture. Prices were a little steep for our humble tastes, I should say. Without major nourishment but also without major exertion, we passed the time by reading and playing cards. The fields that rolled by us were beautiful, full of cows and small brick houses that faded into the evening until we could only see our own bright reflections in the window. During the ride I finished Self-Consciousness: Memoirs by Updike, and thought a lot about death.

Rewinding further, my aunt's house was delightful during our weeklong visit. I bled out around five thousand words for my thesis, visited Amsterdam, and spent a lot of time drinking tea while staring out the window at falling rain in the garden. The town of Bussum, where my aunt lives, is stylish and small, allotting a generous (by European standards) plot of land to each freestanding house; most conform to the aesthetic of traditional Dutch architecture, orange roof tiling and all. In the afternoons we would eat cheese cubes off a wooden board and sip wine in anticipation of an hours-long wait for dinner, usually served at 10pm. A good vacation rhythm until Easter ushered us out. The tomb is empty; my aunt's house is also no longer full.

On Saturday Jeremy and I will be returning to Belgium and a frantic race to the end of our program. Strange to think that I'll be back in the states in less than three months. Time flies.

To get here we rode a long-distance train—no private compartment for us, though; in a show of solidarity we opted for "proletariat class" seating, and were even blessed with access to the bar car for our good-faith gesture. Prices were a little steep for our humble tastes, I should say. Without major nourishment but also without major exertion, we passed the time by reading and playing cards. The fields that rolled by us were beautiful, full of cows and small brick houses that faded into the evening until we could only see our own bright reflections in the window. During the ride I finished Self-Consciousness: Memoirs by Updike, and thought a lot about death.

Rewinding further, my aunt's house was delightful during our weeklong visit. I bled out around five thousand words for my thesis, visited Amsterdam, and spent a lot of time drinking tea while staring out the window at falling rain in the garden. The town of Bussum, where my aunt lives, is stylish and small, allotting a generous (by European standards) plot of land to each freestanding house; most conform to the aesthetic of traditional Dutch architecture, orange roof tiling and all. In the afternoons we would eat cheese cubes off a wooden board and sip wine in anticipation of an hours-long wait for dinner, usually served at 10pm. A good vacation rhythm until Easter ushered us out. The tomb is empty; my aunt's house is also no longer full.

On Saturday Jeremy and I will be returning to Belgium and a frantic race to the end of our program. Strange to think that I'll be back in the states in less than three months. Time flies.

Tuesday, April 3, 2012

Holland Redux: a Table for the Ages

I love the table in my aunt’s house for how solid it is. At some point, a man in need of a table simply pounded together a set of floor slats, passed on the varnish and affixed a set of thick legs; I imagine that he promptly ate off its naked back after setting it upright. Years of footsteps followed by years of dining have lithographed the surface with grooves that hint at heavy, scraping pots and tossed-about silverware; coffee stains and burn marks set off the grey-brown with a deeper brown and brown verging on ashy black.

Such a purely functional eating platform. What could be more inviting come mealtime? It's as sure a sign as any that the real attraction is the food. My aunt emerges from the kitchen laden with a platter or a pan of something spattering and clops it onto the table with a deep thud; no fear, you could airdrop munitions onto this thing and the dust would clear to reveal it standing, proud and intact still. A metal pail full of slush and chilled bottles leaves a ring of condensation near the eastwards end; crumbs pile up in the hidden hollows that once sourced branches for another generation’s forest. Priorities. No frills, no unnecessary decorative elements (apart from a false drawer, but this only reiterates its patchwork origins). Just the Platonic idea of support, realized in the air above the dining room floor. And the food does not disappoint.

I sit at this table in the light of the morning sun and see time, spread out, trapped in the frozen flows of the wood grain. An Ikea table wipes clean; it can be restored to an impeccable state within minutes of a meal. My aunt’s table—well, in the first place, there’s not an impeccable state to which it can, in principle, be restored. It was born old, wizened from a former life of soft beatings under the soles of its owners’ shoes. Its history intertwines with that of the family in the signs of a weathering that has affected every square inch. Nothing is left untouched by its own duration, after all.

The moment it was first lifted up and ringed with chairs, this table began its work of acquiring tell-tale marks, pointers to its history as a communal object of specific uses. The rings convey this most clearly; nicks and smaller stains gesture at moments lost to memory. The whole surface has certainly faded and made it impossible to tell its original color from its present one. Devoid of the sharp angles of new furniture, its worn, rounded corners conform to whichever new hands would hoist this table during a repositioning. This table does not resist; it will outlast your celebration, your snacks for the game, your lifetime.

Such a table can undergo a thumping. Slapping the wood next to one’s plate mid-laugh, pounding it while gesturing with the opposite hand like a dictator, even bringing down two fists in a memorable rage—each of these is a matter of indifference to the enabling piece of furniture. Your humor and your anger will both subside, someday with an unmistakable finality. Such a table will not bend a leg for the event of your expiration. On the eventual day of my death, my aunt’s table will remain upright, austere, imperturbably resigned. The end of the world will elicit no reaction from it. You may as well be serving a noon brunch, for all this table cares.

So yeah, that's why I like my aunt's table.

Monday, March 12, 2012

The Viability of Art Apparently Devoid of Grounding References to Human Beings, Prelude

What follows is the story "Archangel," a quasi-short-short by John Updike that originally appeared in his collection Pigeon Feathers. I put up the whole thing, hoping that either 1) no one comes across this blog who might care about the fact that I've posted an entire piece of someone else's fiction, or 2) I'm legally in the clear, and have not, in fact, violated some literary executor or publishing company's copyright by making the text in its dazzling entirety available to "the public." You will find it after the jump.

Be warned, though; it's a tough nut to crack. My recommendation is to wait until a quiet, serendipitously free half-hour presents itself, and then to make some tea, and then to sit down and read the piece maybe three times through—slowly, perhaps out loud. Let it wash over you. The goal of comprehension in this case should be subordinate to the goal of sheer aesthetic appreciation. I have read it probably ten times, most recently on a weekly beat going back about a month, and honestly, I am still at a loss to say who is being addressed, whether the narrator is trustworthy, where this scene could be taking place, and so forth. But I love the story all the same, not least for the density of its play of sounds and images. In the future I intend to write a followup with some thoughts related to the theme of this post's title. But anyway. I hope you get a chance to savor this before I receive my "Cease and Desist" letter:

Tuesday, March 6, 2012

Jean-Louis Chrétien on Prayer, Second Installment

This is part two of my projected series of indefinite length on Jean-Louis Chrétien's analysis of prayer. To recap, Chrétien is a young French phenomenologist, theologian, and poet whose work remains largely untranslated, and whose exposure to the American academic world is therefore fairly slight. Even the European students in our program do not often recognize his name. My professors, however, have spoken of him in hushed tones of reverence and with restrained enthusiasm (too much would be unbecoming for a professional academic, of course). Chrétien's French is quite beautiful, I have been told; fortunately for me, much of the beauty survives in his English translations, miraculously.

The man himself.

Chrétien is rumored to live quite the hermitic life. Writing in isolation on a typewriter utterly devoid of affectation, in what I fancifully imagine to be a secluded French country house filled to the rafters with books, Chrétien only set up an email address at the urgent request of his publisher after his unreachability very nearly drove his literary agent off the deep end.

But while Chrétien seems to seclude himself from living humans, his work is bursting with connections that he sketches between representatives of far-flung intellectual eras and traditions. Most of his interlocutors are long dead. Their dusted insights help propel a search that has guided his entire philosophical career so far; in a retrospective millennial essay surveying his work over the preceding decade, he states that his overarching goal has been to describe the "excess of the encounter with things, other, world, and God"—an encounter that "requires, most imperatively, our response, and yet seems at the same time to prohibit it." ("Retrospection" in Jean-Louis Chrétien, The Unforgettable and the Unhoped-For (New York: Forham University Press, 2002), 121.)

Before moving on to the analysis of prayer, a brief note on the meaning of the above quotation: "excess" here may be roughly understood to mean a surplus of content that defies our attempts at grasping it through our understanding. Excess is frequently associated with the experience of the sublime, which leaves a person speechless, awe-struck, overcome. Another site of excess would be an encounter with God (theophany), which cannot but overwhelm a finite subject. Chrétien, then, has sought to reveal this surplus as something that leaves traces in even the most common experiences of wholly unexceptional things. In his perspective, something has pushed us to lose sight of this basic dimension of excess, but it remains, for those who are willing to "relearn to see the world."

The essay "The Wounded Word" appears in translation as a part of the previously mentioned collection entitled Phenomenology and the "Theological Turn": the French Debate by Dominique Janicaud et al (New York: Fordham University Press, 2000). I now wish to start exploring the development of Chrétien's analysis, in the hope of eventually teasing out a viable account of the essence of the act of prayer.

A bold statement opens the piece: "Prayer is the religious phenomenon par excellence, for it is the sole human act that opens the religious dimension and never ceases to underwrite, to support, and to suffer this opening" (p147, all page references are to Phenomenology and the "Theological Turn"). Prayer is our mode of access to the religious dimension. How can this be? Aren't there other aspects of religious life that do not begin and end in prayer, that are essentially different from it? Perhaps—but, as Chrétien points out, "[i]f we were unable to address our speech to God or the gods, no other act could intend the divine." Therefore, he writes, "[w]ith prayer, the religious appears and disappears."

Now Chrétien is clearly writing about prayer, but he is also working here to locate his piece within the philosophical context described in the first installment of this series. An analysis of the paradigmatic religious phenomenon, if sufficiently rigorous and methodologically pure, could open up the world of religious experience for legitimate phenomenological investigation. This, I have to believe, is one of Chrétien's goals—to demonstrate that such a phenomenology is possible.

But back to prayer. Chrétien wishes to write a paper rather than a book, and this requires him to impose a limitation on his analysis right from the get go. Prayer, he says, will be considered as a "speech act," loosely understood—but this isn't just an arbitrary narrowing of the field of play. Chrétien actually thinks that the vocal aspect of prayer may get to its very essence, as immediately after introducing the "speech act" qualification, he proposes a guiding question for the rest of the piece: "[i]s vocal prayer merely one form of prayer among others, or is it the prayer par excellence, the sole one in relation to which all others can be defined and constituted, either by derivation or privation?" (149). This question is so detailed as to be mostly rhetorical, an anticipatory statement spoken with an upward intonation at the end so as not to appear too confident. But even if it were a more sincere question, we may still expect the vocal aspect to play a salient role in limning the essence of prayer. Chrétien's treatment of silence is particularly compelling to watch as the argument unfolds.

With the main points of the introduction behind us, we are on our way to being knee-deep in the lake of Chrétien's analysis. Seeing as his essay is very dense and runs to almost forty pages, I intend to save most of his arguments and insights for future installments. But I will close this post with the first descriptive element disclosed by this phenomenology: prayer is situated, Chrétien writes,

This self-manifestation to the invisible leaves the praying person in a state of extreme vulnerability; everything is given and nothing is held back. The preparations of ritual cleanings, the use of certain garments, bodily gestures and movements of all kinds—all of these, Chrétien writes, "can be gathered together in a summoned appearance that incarnates the act of presence" (150, emphasis mine). Incarnates the act of presence—what could that mean? Well, venturing one interpretation, it means this: our presentation of ourselves to the invisible being to which we pray is actually embodied in the physical acts of prayer. When we kneel, light candles, don vestments, doff our caps, and so forth, we are symbolizing our self-presentation to the divine, and in a way, effecting it.

This is why bodily or ritualistic actions symbolize rather than signify the act of presence: because the gestures and acts are unified with the central act of self-manifestation, and bring it to "incarnation," as it were, allowing this act of self-manifestation to involve the whole of the person praying. Prayer is not just an offering of an idea or a thought or a plea to God, in this account; Chrétien wishes instead to say that prayer is the offering of our whole selves to God.

But while Chrétien seems to seclude himself from living humans, his work is bursting with connections that he sketches between representatives of far-flung intellectual eras and traditions. Most of his interlocutors are long dead. Their dusted insights help propel a search that has guided his entire philosophical career so far; in a retrospective millennial essay surveying his work over the preceding decade, he states that his overarching goal has been to describe the "excess of the encounter with things, other, world, and God"—an encounter that "requires, most imperatively, our response, and yet seems at the same time to prohibit it." ("Retrospection" in Jean-Louis Chrétien, The Unforgettable and the Unhoped-For (New York: Forham University Press, 2002), 121.)

Before moving on to the analysis of prayer, a brief note on the meaning of the above quotation: "excess" here may be roughly understood to mean a surplus of content that defies our attempts at grasping it through our understanding. Excess is frequently associated with the experience of the sublime, which leaves a person speechless, awe-struck, overcome. Another site of excess would be an encounter with God (theophany), which cannot but overwhelm a finite subject. Chrétien, then, has sought to reveal this surplus as something that leaves traces in even the most common experiences of wholly unexceptional things. In his perspective, something has pushed us to lose sight of this basic dimension of excess, but it remains, for those who are willing to "relearn to see the world."

* * *

The essay "The Wounded Word" appears in translation as a part of the previously mentioned collection entitled Phenomenology and the "Theological Turn": the French Debate by Dominique Janicaud et al (New York: Fordham University Press, 2000). I now wish to start exploring the development of Chrétien's analysis, in the hope of eventually teasing out a viable account of the essence of the act of prayer.

A bold statement opens the piece: "Prayer is the religious phenomenon par excellence, for it is the sole human act that opens the religious dimension and never ceases to underwrite, to support, and to suffer this opening" (p147, all page references are to Phenomenology and the "Theological Turn"). Prayer is our mode of access to the religious dimension. How can this be? Aren't there other aspects of religious life that do not begin and end in prayer, that are essentially different from it? Perhaps—but, as Chrétien points out, "[i]f we were unable to address our speech to God or the gods, no other act could intend the divine." Therefore, he writes, "[w]ith prayer, the religious appears and disappears."

Now Chrétien is clearly writing about prayer, but he is also working here to locate his piece within the philosophical context described in the first installment of this series. An analysis of the paradigmatic religious phenomenon, if sufficiently rigorous and methodologically pure, could open up the world of religious experience for legitimate phenomenological investigation. This, I have to believe, is one of Chrétien's goals—to demonstrate that such a phenomenology is possible.

But back to prayer. Chrétien wishes to write a paper rather than a book, and this requires him to impose a limitation on his analysis right from the get go. Prayer, he says, will be considered as a "speech act," loosely understood—but this isn't just an arbitrary narrowing of the field of play. Chrétien actually thinks that the vocal aspect of prayer may get to its very essence, as immediately after introducing the "speech act" qualification, he proposes a guiding question for the rest of the piece: "[i]s vocal prayer merely one form of prayer among others, or is it the prayer par excellence, the sole one in relation to which all others can be defined and constituted, either by derivation or privation?" (149). This question is so detailed as to be mostly rhetorical, an anticipatory statement spoken with an upward intonation at the end so as not to appear too confident. But even if it were a more sincere question, we may still expect the vocal aspect to play a salient role in limning the essence of prayer. Chrétien's treatment of silence is particularly compelling to watch as the argument unfolds.

With the main points of the introduction behind us, we are on our way to being knee-deep in the lake of Chrétien's analysis. Seeing as his essay is very dense and runs to almost forty pages, I intend to save most of his arguments and insights for future installments. But I will close this post with the first descriptive element disclosed by this phenomenology: prayer is situated, Chrétien writes,

in an act of presence to the invisible. It is the act by which the man praying stands in the presence of a being in which he believes but does not see and manifests himself to it.

- "The Wounded Word," 149.So prayer is embedded in a person's act whereby she purposefully makes herself present to a being that she believes in, although she does not see it; she believes herself to be in this being's presence, and "manifests" herself to it. We could also say that she discloses herself to this being, that she wills herself to "be" before it. The monotheistic belief in the omniscience of God illuminates an important aspect of this move: though a praying person may believe herself to always be in the sight or presence of God, in prayer she intentionally directs herself towards God, as though to meet his invisible gaze, and willfully presents herself to him.

This self-manifestation to the invisible leaves the praying person in a state of extreme vulnerability; everything is given and nothing is held back. The preparations of ritual cleanings, the use of certain garments, bodily gestures and movements of all kinds—all of these, Chrétien writes, "can be gathered together in a summoned appearance that incarnates the act of presence" (150, emphasis mine). Incarnates the act of presence—what could that mean? Well, venturing one interpretation, it means this: our presentation of ourselves to the invisible being to which we pray is actually embodied in the physical acts of prayer. When we kneel, light candles, don vestments, doff our caps, and so forth, we are symbolizing our self-presentation to the divine, and in a way, effecting it.

This is why bodily or ritualistic actions symbolize rather than signify the act of presence: because the gestures and acts are unified with the central act of self-manifestation, and bring it to "incarnation," as it were, allowing this act of self-manifestation to involve the whole of the person praying. Prayer is not just an offering of an idea or a thought or a plea to God, in this account; Chrétien wishes instead to say that prayer is the offering of our whole selves to God.

* * *

And that brings us about a tenth of the way into the essay. Almost all of the riches are still ahead for us. Anyway, thanks for reading! I hope you return for installment three. By then we should really be cooking with gas.

Labels:

Analysis,

Chrétien,

Faith,

Leuven,

Phenomenology,

Philosophy,

Prayer,

Theology,

Thesis

Saturday, March 3, 2012

How to Store Your Books If You Are Awesome and Rich

I thought of this the other day while talking with roommate Dan about interesting ways to store books. I couldn't find illustrations online for anything close to what I had in mind, so I downloaded a free drawing program from the app store and attempted to sketch out my idea. Here goes:

First, imagine that you own a house with a large basement or ground-level room. The floor is basically composed of congruent glass panels set in a grid pattern, like so:

The glass is reinforced—it's like, an inch thick and bulletproof—which allows people to walk over it and place furniture on top of it. You are probably wondering why there is a hazy blush of color in the center of each of those transparent or translucent (homeowner's choice) glass panels, huh? Well, I'll tell you why! It's because underneath each panel is an inset storage shelf, upon which has been placed a row of books! Seen from the perspective of a person standing on this floor, the vertical alcoves would look something like this:

First, imagine that you own a house with a large basement or ground-level room. The floor is basically composed of congruent glass panels set in a grid pattern, like so:

I had to clear out the furniture to draw this picture.

The glass is reinforced—it's like, an inch thick and bulletproof—which allows people to walk over it and place furniture on top of it. You are probably wondering why there is a hazy blush of color in the center of each of those transparent or translucent (homeowner's choice) glass panels, huh? Well, I'll tell you why! It's because underneath each panel is an inset storage shelf, upon which has been placed a row of books! Seen from the perspective of a person standing on this floor, the vertical alcoves would look something like this:

A first edition of Yale Press's 1954 The Future: Progressive Essays in Experimental Ontology anthology? Amazing!

How might a person go about accessing the books they put under their glass floor? Did I hear that question correctly? I sure hope so, because that's precisely the question I was about to answer. Notice that on the right side of each glass pane, there is a pair of dots. Those dots represent small holes, the rims of which would be specially reinforced with rubber O-rings. Why is this important? Because you, as the owner of this classy, bookish basement, have in your possession a grip with two prongs that are designed to fit into the holes on these glass panels. Each prong would terminate in a curve designed to slide into a groove under the glass, for a close and sure fit.

The backwards beamed eighth notes pictured are actually the grip.

When the prongs go in, the attached grip becomes a handle with which you may open the glass panel! Each pane will turn on a hinge that allows it to open like a square glass door. You know what that means? It means that with this grip, you have exclusive, easy access to your basement library! When you're finished retrieving the tomes you want, you can close the panel, remove the grip, and hang it back up on the bronze hook you installed in your kitchen, closet or panic room.

What pretty pastel-colored spines your books have!

And there you have it. So, if you're a wealthy homeowner with a large spare room that's got a high ceiling (this design would move the level of the floor up a couple feet), and you happen to own a lot of books, you should consider storing them in this way—under a beautiful, thick plane of square glass panels. You could even line the walls with traditional standing bookshelves, especially ones made of fragrant wood, like pine. People would walk into that room and say things like, "I am in a great hall of knowledge!", "this person is serious about book storage!", "what a great-smelling repository of literature and philosophy!", and so forth. Who doesn't like compliments?

* * *

UPDATE: In light of my usual standard of scrupulousness when it comes to citing my sources, I am a tad bit ashamed to admit that Dan was the one who originally introduced the idea of the glass floor. When I started writing and sketching the above yesterday, I was operating with the sincere belief that I was the originator of the idea, but alas! It came out in conversation today that Dan is the true source. Consider the above an appropriation and development of his original idea, which emerged in rapid-fire brainstorming (hence the mistake). Sorry Dan!

Monday, February 13, 2012

Round Two

Our break has ended, and a new term has begun. The department secretary will be posting our first term grades on Wednesday, at which point we'll be able to see who will need to come back in August to retake failed examinations or rewrite failed papers.

Most of the courses being offered this term are in a seminar format, which means both smaller class sizes and higher expectations for enrolled students. A difficult choice looms: I have room in my schedule for two seminars, but there are three relevant options:

Most of the courses being offered this term are in a seminar format, which means both smaller class sizes and higher expectations for enrolled students. A difficult choice looms: I have room in my schedule for two seminars, but there are three relevant options:

- An intensive course on disgust. Fascinating and exciting material, taught by an intimidating (but wryly funny) professor who has leveled some very serious demands regarding course attendance and preparedness. I expect it'll be engaging and a lot of fun. The only question I have, the one preventing me from locking it in to my schedule, is: how relevant would this be for my thesis?

- The Husserl Archives Seminar. This would probably be the most directly useful for my research, but it will also probably be the most dry and boring of the three. Might just have to bite the bullet and take it anyway, my apprehensions about reading large quantities of Husserl notwithstanding.

- Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations. This class will meet for extended sessions once a month until the summer, and promises to dig deeply into the later work of Ludwig Wittgenstein. He's the original reason for my philosophical interest in language; I would love to deepen my acquaintance with him, but given his location in the canon (he has primarily been appreciated and appropriated within the analytic tradition in philosophy), this seminar would probably diverge the most widely from my current philosophical interests and research.

As you can see, concern for the thesis provides this semester's dominant theme. Hopefully my research panic doesn't edge out my commitment to classes for this term; it will probably be important to come up with both a sense of boundaries and a regular work schedule in order to avoid dropping any of the various balls I'm going to try to juggle.

Bonus round: here's a picture of me and roommate Dan at the Eiffel Tower just over two weeks ago:

"Look, my cowlick is gone!"

Write us letters and emails; we are hardy boys but it is going to be a tough fight, and our souls are sensitive to the rain and the slush and the existentialism that apparently soak this town during the winter months.

Wednesday, February 1, 2012

Wisława Szymborska, 1923-2012

I heard a guy say once that philosophers have the ability to become enduring companions, closer than close friends, for how much we allow them to speak into and give shape to our lives. This seems even more true of poets than philosophers, to chance a clean distinction (one that the poet I love dissolves, time and again). The most personal and deeply felt aspects of living in this world don't translate well into propositions, but in blessed moments, they may come to some kind of partial articulation—a fly-away instant of real meaning—through verse. Today I lost one of my companions, a Polish woman I never shook hands with, but whose words have been resonating in my mind and heart for years.

Wisława Szymborska is a poet I met between the brown covers of a book that someone had crammed into a low shelf at a used bookstore. Love hit me pretty hard, pretty fast. For the sake of brevity, I might call out a single theme in her work that's left a mark on me—namely, her reflections on time. Her poems frequently manage to bring out the radical uncertainty and contingency of human life, the speckdom of ours in a dark universe where eternity provides bookends for the whole of human civilization, while still holding on to a tiny thread of hope. That tiny thread was its own paradoxically ineffable argument, a tassel from the hem of Job's rent garments; the possibility of redemption in Szymborska's perspective still seems more solid and trustworthy than glib certainties in anyone else's.

What else could a clumsy writer say to honor a brilliant interpreter of human experience? She's been a beautiful and gracious companion to me since our first encounter years ago, and I look forward to many years of companionship still to come. God bless you, Mrs Szymborska. The world is better for your having been in it.

Wisława Szymborska is a poet I met between the brown covers of a book that someone had crammed into a low shelf at a used bookstore. Love hit me pretty hard, pretty fast. For the sake of brevity, I might call out a single theme in her work that's left a mark on me—namely, her reflections on time. Her poems frequently manage to bring out the radical uncertainty and contingency of human life, the speckdom of ours in a dark universe where eternity provides bookends for the whole of human civilization, while still holding on to a tiny thread of hope. That tiny thread was its own paradoxically ineffable argument, a tassel from the hem of Job's rent garments; the possibility of redemption in Szymborska's perspective still seems more solid and trustworthy than glib certainties in anyone else's.

What else could a clumsy writer say to honor a brilliant interpreter of human experience? She's been a beautiful and gracious companion to me since our first encounter years ago, and I look forward to many years of companionship still to come. God bless you, Mrs Szymborska. The world is better for your having been in it.

Portrait of the Artist as a Compassionate Human Being

Monday, January 30, 2012

Paris, in Brief

I never in my life thought it would be possible to feel the way I did standing underneath the Eiffel Tower. That's where the epiphany struck. In one of the world's great cities, with steel beams rising above my upturned face into a cloudless sky, I stood with an open mouth, like an idiot.

People wearing berets stepped around me, adjusting their fanny packs. I closed my eyes and felt the air on my face. The din of the square reminded me of something from my past; voices from without, inflected with a midwestern flatness, resonated with voices deep within. The jostling crowd, the excitement, the music; these held hidden ties to a single memory that teased me and danced in the periphery of my mind. I searched the insides of my eyelids for a clue.

One song ended and another began. What was that? Something loomed behind the excited cacophony of a thousand American conversations. I tilted an ear up at the girder-mounted speakers just in time for the tell-tale sign: an unmistakable, unredeemable, unforgivable twang. God help us, they're playing country music at the Eiffel Tower.

In a rush of associations, I snatched the memory out of the ether. The whole scene brought me back to the Allen County Fair. Country music, a buzzing midwestern crowd, and I swear those crepes were being dispensed out of carts just like the ones that sell fried elephant ears all over semi-rural Ohio, beneath the banked turns of frighteningly-temporary miniature roller coasters. If I shut out my view of the world's ultimate romantic destination, I was left to assemble a patchwork out of my other sensory feeds, and their data were as well-matched to a chilly morning at a fair in Ohio as anything I was presently experiencing. (The absence of the smell of manure only meant I was on the food-side of the fairgrounds, rather than the barn-side.)

And that's how I came to feel the impossible while standing under the Eiffel Tower in Paris, France. Surrounded by my jowly countrymen, in the presence of whom I pensively chewed a cosmopolitan meat stick, I closed my eyes and felt perfectly at home.

People wearing berets stepped around me, adjusting their fanny packs. I closed my eyes and felt the air on my face. The din of the square reminded me of something from my past; voices from without, inflected with a midwestern flatness, resonated with voices deep within. The jostling crowd, the excitement, the music; these held hidden ties to a single memory that teased me and danced in the periphery of my mind. I searched the insides of my eyelids for a clue.

One song ended and another began. What was that? Something loomed behind the excited cacophony of a thousand American conversations. I tilted an ear up at the girder-mounted speakers just in time for the tell-tale sign: an unmistakable, unredeemable, unforgivable twang. God help us, they're playing country music at the Eiffel Tower.

In a rush of associations, I snatched the memory out of the ether. The whole scene brought me back to the Allen County Fair. Country music, a buzzing midwestern crowd, and I swear those crepes were being dispensed out of carts just like the ones that sell fried elephant ears all over semi-rural Ohio, beneath the banked turns of frighteningly-temporary miniature roller coasters. If I shut out my view of the world's ultimate romantic destination, I was left to assemble a patchwork out of my other sensory feeds, and their data were as well-matched to a chilly morning at a fair in Ohio as anything I was presently experiencing. (The absence of the smell of manure only meant I was on the food-side of the fairgrounds, rather than the barn-side.)

And that's how I came to feel the impossible while standing under the Eiffel Tower in Paris, France. Surrounded by my jowly countrymen, in the presence of whom I pensively chewed a cosmopolitan meat stick, I closed my eyes and felt perfectly at home.

Labels:

Contentment,

Eiffel Tower,

Hope,

Identity,

Irony,

Paris,

Tourism,

Weekend Trip

Tuesday, January 17, 2012

Lana Del Rey and the Locus of Criticism

My procrastination ought to make the most sense now, of all times, on account of this being exam week, with my next test slated for Friday afternoon. If a person has four wide-open days until his next objective, it's permissible for him to spend some of that time engrossed in extracurricular subjects, right? Which is my justification for the past 36 hours. Yesterday, after putting a period on the final line of a fifteen-page essay exam, I permitted my mind to fly off to whenever and wherever it wanted. To a noble place, my mind did not deliver me.

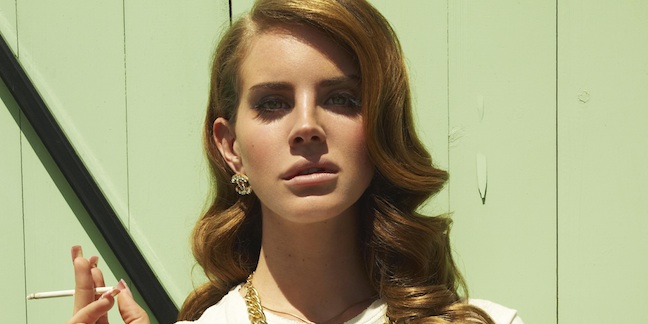

Lana Del Rey is probably a familiar name and face to you, if you waste your spare time scanning pop culture and music blogs. She has an EP out (I think?) and is releasing a full-length album at the end of January; she also performed on SNL last weekend and has been getting a ton of media attention, much of which has been negative (even angrily so). The elite, pace-setting members of the indie music scene have come down especially hard on Ms. Del Rey (a stage name), and while I can't speak to the musical criticisms qua musical criticisms, I do find the extra-musical complaints fairly compelling and accessible, because they are not very technical, and very human.

The thing is, 25-year-old Del Rey got her industry sea legs performing under her real name, Lizzy Grant, and when I say industry sea legs, I mean she stumbled between venues for a few years without gaining any real traction with the people who mattered. As competent but somewhat generic musicians are wont to do, she handily evaded commercial success.

But then Lizzy became Lana, and consequently went from being pretty in a cornfield blonde, wholesome, small-town-girl-next-door sort of way to being, well, something else. A collagen-puffed pout sealed her revamped market-ready image, which combines lapsed (and mourned) innocence with a caricaturish femme-fatale vibe and a lot of other things that make me feel weird when I watch her performing or giving interviews.

Music bloggers take real offense, it seems, because she is so clearly sculpted to appeal to denizens of their empire, the pop-indie scene. Her self-aware affectations imply a sort of wink-wink nod to something being parodied, or at least communicate the sort of po-mo playfulness that artists use to give listeners a sense of being in on something together, little cultural co-conspirators that we are. Her videos swing between whimsical and overblown images (Del Rey ensconced in a throne in what appears to be a cathedral, with tigers laying down on either side within arm's reach; Del Rey, bloodied, held in the arms of a muscular tattoo-covered dude with gauged ears, in front of the burning wreckage of their car—I don't see how you could interpret these as anything but self-aware, jokey excesses) and grainy Super 8 "found footage" style montages that evoke powerful nostalgia—even for the mid-2000s, apparently, judging from the inclusion (has to be another wink-wink moment, right?) of a familiar iPod billboard advertisement, nestled between shots of unhelmeted couples riding classic Victory motorcycles.

Even though I haven't the slightest critical chops to justify my saying anything about her music, I will say this: her tracks are, unsurprisingly, perfectly matched to the aesthetics of her persona and brand. The songs I've listened to cultivate a (self-consciously?) retro sensibility, with static-crackling samples of decades-old recordings, kitschy string intros, and moody lyrics that Del Rey delivers with a trademark croon. You may imagine it accurately with the aid of her promotional taglines, which she's apparently used to describe herself during interviews: "a gangster Nancy Sinatra," "Lolita got lost in the hood." As one online commentator points out, these sound a lot more like phrases that were tossed around in a corporate boardroom during a brainstorming session than anything a musician would say about herself off the cuff.

The thing is, though, all of this brand genealogy stuff seems pretty weak, insofar as it's intended as criticism. Successful musicians (perhaps with the exception of those who work exclusively in the studio) are necessarily successful performers—not only of their music, but of themselves—and creating a persona or brand is one way, perhaps the only way, of approaching performance: come up with a character to play, a simple and consumable identity that you can separate from yourself and offer as a commodity to potential listeners, fans, EP purchasers. Bring out a single theme that people can latch on to and associate with you; find an unexplored niche in the pop-cultural landscape and put your stake in the ground. It's one method among many for creating a splash, and I would go so far as to say that it's basically unrelated to the actual quality of the creative product.

But still, some artists leave us with a sense of having gone about this process of cultivating showmanship in a more "authentic" way; their onstage or video versions of themselves seem roughly natural extensions of the personalities we imagine them to exude around their families or their pets. Why does Lana Del Rey still leave such a bad taste in the mouths of so many? Do people really believe themselves to have such psychological insight and moral sensitivity in their assessments of the Del Rey persona's "truthfulness?" Is it just that people think she's a big phony, or could it have a little more to do with in-house resentment? Could it be the attention she's been receiving that other artists and a lot of critics feel is undeserved, based on her questionable talent and minuscule CV and blatant posturing?

Perhaps. But the market is obviously, always, and inherently unfair, and popular success is a cruel mistress to those who would try to court her. Del Rey set out to achieve something that she seems to have achieved, even if it's been a tough slog through bad performances and frequently caustic press that may have required her to give up something of herself. The brand she has constructed is essential to that success, and to call it what it is—manufactured—is to miss the point.

Ah yes, the point. The reason my brain keeps straining to make sense of Lana Del Rey is that frustratingly complicated aspect of her schtick that I mentioned earlier. The arch persona and intimations of irony do lead me to look for the joke, or the parody, or whatever it is that she's doing; I'm having a magnificently hard time trying to figure out the proper locus of criticism, the guiding intention that would establish a context in which her whole act might be evaluated, according to its own goals. I want to "get" the point, and am not content to believe that it's just to generate buzz.

Is it necessary for her to have the sort of determinate aim that I'm trying to uncover? Probably not, and maybe this reveals a weakness of my own in trying to understand music and musicians generally—an inability to be satisfied with a decidedly equivocal play of symbols designed to hazily evoke rather than communicate. Call it a preference; I have a greater appreciation for art that seems to ride a discernible (and criticizable) intention—for lyrics that tell stories, for instance—than art that forces its consumers to cast out feelers for shreds of meaning in purposefully jumbled and even inchoate sets of ideas and images.

Obviously there's a spectrum here, and I don't mean to be reductive, but man do I get annoyed with music and literature that isn't just obscure or difficult, but intentionally, a-priori meaningless in a cynical sort of way. Meet me halfway, creators; I love interpreting in the face of ambiguity and all its attendant tensions, and I find it bracing to bear up under the onslaught of tricks that subvert traditional artistic forms. But I hate finding out that I'm trying to make sense of something that was never meant to be more than packaged gibberish, a glossed-up sneer. Such stuff does exist, and it's angering.

Back to Del Rey. I have my theories. With the lips and the distant look, is she some sort of embodied critique of porny male sexual desire - a sendup of the appearance and attitude of a jaded longtime member of the adult film community, where the obvious artificiality implicates the viewer, as though to ask "is this what you want? A fleshed-out Barbie doll?" This could be the calculated side of a coin that flips to reveal the full-throated rage that characterized the Blood Brothers.

Or, with the grainy montage in "Video Games," is she a sad messenger angel from the past—a 60s flight attendant, somehow simultaneously from the 80s—who contrasts Morning in America in all its apparent sun-shiny resplendence with the grimness of present economic instability? Or, does the same angel sing over this montage only to show the fickleness of nostalgia and the impossibility of remembering rightly, who means to tell us that our idea of the past is a lie?

What are you looking at?

Lana Del Rey is probably a familiar name and face to you, if you waste your spare time scanning pop culture and music blogs. She has an EP out (I think?) and is releasing a full-length album at the end of January; she also performed on SNL last weekend and has been getting a ton of media attention, much of which has been negative (even angrily so). The elite, pace-setting members of the indie music scene have come down especially hard on Ms. Del Rey (a stage name), and while I can't speak to the musical criticisms qua musical criticisms, I do find the extra-musical complaints fairly compelling and accessible, because they are not very technical, and very human.

The thing is, 25-year-old Del Rey got her industry sea legs performing under her real name, Lizzy Grant, and when I say industry sea legs, I mean she stumbled between venues for a few years without gaining any real traction with the people who mattered. As competent but somewhat generic musicians are wont to do, she handily evaded commercial success.

But then Lizzy became Lana, and consequently went from being pretty in a cornfield blonde, wholesome, small-town-girl-next-door sort of way to being, well, something else. A collagen-puffed pout sealed her revamped market-ready image, which combines lapsed (and mourned) innocence with a caricaturish femme-fatale vibe and a lot of other things that make me feel weird when I watch her performing or giving interviews.

The Artist as Lizzy Grant, crowned Miss Iowa in another life

Music bloggers take real offense, it seems, because she is so clearly sculpted to appeal to denizens of their empire, the pop-indie scene. Her self-aware affectations imply a sort of wink-wink nod to something being parodied, or at least communicate the sort of po-mo playfulness that artists use to give listeners a sense of being in on something together, little cultural co-conspirators that we are. Her videos swing between whimsical and overblown images (Del Rey ensconced in a throne in what appears to be a cathedral, with tigers laying down on either side within arm's reach; Del Rey, bloodied, held in the arms of a muscular tattoo-covered dude with gauged ears, in front of the burning wreckage of their car—I don't see how you could interpret these as anything but self-aware, jokey excesses) and grainy Super 8 "found footage" style montages that evoke powerful nostalgia—even for the mid-2000s, apparently, judging from the inclusion (has to be another wink-wink moment, right?) of a familiar iPod billboard advertisement, nestled between shots of unhelmeted couples riding classic Victory motorcycles.

Even though I haven't the slightest critical chops to justify my saying anything about her music, I will say this: her tracks are, unsurprisingly, perfectly matched to the aesthetics of her persona and brand. The songs I've listened to cultivate a (self-consciously?) retro sensibility, with static-crackling samples of decades-old recordings, kitschy string intros, and moody lyrics that Del Rey delivers with a trademark croon. You may imagine it accurately with the aid of her promotional taglines, which she's apparently used to describe herself during interviews: "a gangster Nancy Sinatra," "Lolita got lost in the hood." As one online commentator points out, these sound a lot more like phrases that were tossed around in a corporate boardroom during a brainstorming session than anything a musician would say about herself off the cuff.

"Ha-ha! Americana, am I right?"

The thing is, though, all of this brand genealogy stuff seems pretty weak, insofar as it's intended as criticism. Successful musicians (perhaps with the exception of those who work exclusively in the studio) are necessarily successful performers—not only of their music, but of themselves—and creating a persona or brand is one way, perhaps the only way, of approaching performance: come up with a character to play, a simple and consumable identity that you can separate from yourself and offer as a commodity to potential listeners, fans, EP purchasers. Bring out a single theme that people can latch on to and associate with you; find an unexplored niche in the pop-cultural landscape and put your stake in the ground. It's one method among many for creating a splash, and I would go so far as to say that it's basically unrelated to the actual quality of the creative product.

But still, some artists leave us with a sense of having gone about this process of cultivating showmanship in a more "authentic" way; their onstage or video versions of themselves seem roughly natural extensions of the personalities we imagine them to exude around their families or their pets. Why does Lana Del Rey still leave such a bad taste in the mouths of so many? Do people really believe themselves to have such psychological insight and moral sensitivity in their assessments of the Del Rey persona's "truthfulness?" Is it just that people think she's a big phony, or could it have a little more to do with in-house resentment? Could it be the attention she's been receiving that other artists and a lot of critics feel is undeserved, based on her questionable talent and minuscule CV and blatant posturing?

Perhaps. But the market is obviously, always, and inherently unfair, and popular success is a cruel mistress to those who would try to court her. Del Rey set out to achieve something that she seems to have achieved, even if it's been a tough slog through bad performances and frequently caustic press that may have required her to give up something of herself. The brand she has constructed is essential to that success, and to call it what it is—manufactured—is to miss the point.

Ah yes, the point. The reason my brain keeps straining to make sense of Lana Del Rey is that frustratingly complicated aspect of her schtick that I mentioned earlier. The arch persona and intimations of irony do lead me to look for the joke, or the parody, or whatever it is that she's doing; I'm having a magnificently hard time trying to figure out the proper locus of criticism, the guiding intention that would establish a context in which her whole act might be evaluated, according to its own goals. I want to "get" the point, and am not content to believe that it's just to generate buzz.

Is it necessary for her to have the sort of determinate aim that I'm trying to uncover? Probably not, and maybe this reveals a weakness of my own in trying to understand music and musicians generally—an inability to be satisfied with a decidedly equivocal play of symbols designed to hazily evoke rather than communicate. Call it a preference; I have a greater appreciation for art that seems to ride a discernible (and criticizable) intention—for lyrics that tell stories, for instance—than art that forces its consumers to cast out feelers for shreds of meaning in purposefully jumbled and even inchoate sets of ideas and images.

Obviously there's a spectrum here, and I don't mean to be reductive, but man do I get annoyed with music and literature that isn't just obscure or difficult, but intentionally, a-priori meaningless in a cynical sort of way. Meet me halfway, creators; I love interpreting in the face of ambiguity and all its attendant tensions, and I find it bracing to bear up under the onslaught of tricks that subvert traditional artistic forms. But I hate finding out that I'm trying to make sense of something that was never meant to be more than packaged gibberish, a glossed-up sneer. Such stuff does exist, and it's angering.

Back to Del Rey. I have my theories. With the lips and the distant look, is she some sort of embodied critique of porny male sexual desire - a sendup of the appearance and attitude of a jaded longtime member of the adult film community, where the obvious artificiality implicates the viewer, as though to ask "is this what you want? A fleshed-out Barbie doll?" This could be the calculated side of a coin that flips to reveal the full-throated rage that characterized the Blood Brothers.

Or, with the grainy montage in "Video Games," is she a sad messenger angel from the past—a 60s flight attendant, somehow simultaneously from the 80s—who contrasts Morning in America in all its apparent sun-shiny resplendence with the grimness of present economic instability? Or, does the same angel sing over this montage only to show the fickleness of nostalgia and the impossibility of remembering rightly, who means to tell us that our idea of the past is a lie?

horsewoman of the apocalypse

The pictured album cover weaves together the visual tropes intended to qualify Del Rey in the public imagination. The stark center-framing, combined with her blank look, 50s housewifey hairstyle, and closed collar, evokes all the creepiness of The Stepford Wives, the freaky suburban thriller/horror film that (SPOILER ALERT) climaxes with the protagonist making a terrifying discovery just before being implicitly murdered. What does she find out? That the women in her town are being systematically killed and replaced with robotic surrogates, chillingly cheery automatons that are perfect in the eyes of the town's male inhabitants—square-jawed breadwinners who would each, of course, like nothing more than to own a beautiful woman who doesn't talk back, puts out on demand, and has none of her own needs.

The movie and the novel it's based on are satirical and intended to call out a sexist culture by hyperbolizing its inner logic of oppression. Does Del Rey present herself with a similar goal in mind? This is related to the first interpretation offered above, that of Del Rey as embodied critique of male heterosexual erotic fantasy. She could even be implicating a whole listless generation for its sins, if we take into account her song "Video Games," which laments a relationship that falters and fails because of a dude's inability to pull himself away from the wispy pleasures of his console.

This is the most charitable reading of the mythos that is possible, I figure, and unfortunately, at the end of the day, it just doesn't seem to square up with the data. Del Rey is a meticulously refined product, designed to appeal to a certain audience, and any positive or productive take on her act seems superfluous to an essentially commercial core. Here's the insidious part though, given what I've just said: Lana Del Rey totally does meet you halfway, but not in any of the myriad constructive ways that serious art does.

Here's what I mean. Lana Del Rey's intimations of irony and hidden, subversive meanings allow the listener to feel as though they're in on the joke—but one isn't being made. She ultimately seems to proffer one more version of the aforementioned postmodern playfulness that rewards quirky and whimsical musical acts with throngs of listeners. Rather than upholding an underlying, morally-superior reality, which gives irony its substance and its teeth as a tool for critique, Del Rey settles for aping the form without committing to a specified content. It's a well-trod path that recommends itself to creatives of all kinds who are trying to make a way for themselves in the lingering shadow of the fading "hipster" monolith. The result is the perpetuation of our on-hand cultural ideals of self-awareness and savvy detachment, but without positing a good worth pursuing within the aesthetic and spiritual context those ideals help to establish.

One could take this even further, however. There is one way of understanding the anti-teleological posturing of Del Rey that ascribes to her a serious and deep artistic purpose, one that transcends and even subverts the designs of the executives who first came up with her name. Unfortunately for Lizzy Grant, it's a soul-threatening move: what if Lana Del Rey is a true metaphysical nihilist?

If we take her pinched face and impossibly distant stare to a super-meta level, we might find an artist committed to showing everything to be a big fake mess. Not just fame, or commercial sexuality, or image-obsession, or a cynical music industry, but everything. Do the tigers in the deserted cathedral of the "Born to Die" video guard a faux-Nietzschean queen, crowned with relevance and wealth, offering herself as a stand-in for the sacred we no longer believe in—even dying as a martyr for this vision, her bloodstained figure a symbol of the ultimate sacrifice of oneself to one's pleasures, claiming for herself a pop-religion of smirking, tired, uncontested hedonism? We could be in on the joke after all, if the joke turns out to be the universe of human meaning.

Could Lana Del Rey be so post-ironic as to actually intend her album title as an open question: is there something else to life, or are we really born to die? Could this question be the proper locus of criticism, the interrogation of value itself the ultimate goal? If so, could we perceive in Lana Del Rey a consummate creative force—an artist with the spiritual depth to stare deeply into the abyss, whose impassive gaze back at us reveals flickers of her grappling with that overwhelming darkness, which would threaten us all?

Thursday, January 12, 2012

January is a Month for Exams

And papers. I'm 6,000 words deep, between the two that are due. If I can get them both done for tomorrow I'll have the weekend to study for my first exam, which is slated for Monday morning. It's as though the month of January is solely intended to remind you why some writer originally replaced a generic word connoting movement through time with "grinding." Grinding is an apt word to describe the sort of conveyance that it's gonna take to make it to February.

Anyway, during the past week I found out about two apps that I think are worth sharing. The first is called "Flux." Apparently your monitor produces light that mimics that of the sun, and it doesn't let up after the real sun sets, so your eyes don't get the rest they deserve while you're nocturnally devouring the internet. This app (thankfully free) corrects this problem by automatically raising the "color temperature" of your display at around the time the sun sets in your part of the world. It's pretty neat. To be honest, I have no idea if it's actually helpful or if I've just been duped by a lot of hype into thinking that it is, but in any case, here's the site where you can download it, or investigate it, or both. I figure it's worth trying. As a bonus, it works with OS X, Windows, and Linux! Hear that, nerd? Linux! Oh, and Apple's iOS... so you can get to sleep faster after finishing a game of Angry Birds between the sheets?*

The second app requires a little more courage to plug, because to recommend it is to identify with the problem it is designed to mitigate. It's called "Freedom" and it lets you shut off your internet for a variable amount of time, anywhere between fifteen minutes and eight full hours. The interesting thing about Freedom is what it assumes about you, its user: namely, that you are incapable of working in a focused and disciplined way on your computer so long as your computer has a connection to the whooshing black hole that is the internet. Really, your willpower is so slight and your resolve so pathetic that you can't just unplug your ethernet cord or disable your wifi. You need something a little stronger—the firmness of a maternal authority, perhaps. You need Momma App to fly into a rage, pinch your ear and say "that's IT! NO MORE INTERNET for you! [...] umm, how long would you like me to keep you offline?"

And you know what? Yeah, I am that creature of pitiable resolve. Today, severed from the digital mothership as I was, I wrote some 2500 words in a six hour window. Yes, it was hard and tiresome and lonely and claustrophobic and dizzyingly scary just like every online junkie knows withdrawal will be, but at the end of the day, I'm thankful for how much crap I got done. I only wish Freedom wouldn't put you out for $10, but eh, someone else's discipline has to come at a price, I suppose. Here's the site. You can also download a free trial version with five uses, and the app is compatible with OS X and Windows Vista/XP/7/whatever.

I've written two longer pieces for this blog that I need to clear with other people before I put them up, but they're in the hopper at least. Not sure what else will go up here in the next few weeks, with all the tests and the papers and the endless sighing that dominate this month in my calendar, but who knows. Thanks for reading. As a bonus, here's a balloon sculpture commemorating a painting commemorating a couple that was well acquainted with old-school freedom and all its attendant zaniness:

__________________________________________

*Could this be the euphemism for sex that this generation has been waiting for? Not the euphemism we want, but perhaps - the euphemism we deserve?

Anyway, during the past week I found out about two apps that I think are worth sharing. The first is called "Flux." Apparently your monitor produces light that mimics that of the sun, and it doesn't let up after the real sun sets, so your eyes don't get the rest they deserve while you're nocturnally devouring the internet. This app (thankfully free) corrects this problem by automatically raising the "color temperature" of your display at around the time the sun sets in your part of the world. It's pretty neat. To be honest, I have no idea if it's actually helpful or if I've just been duped by a lot of hype into thinking that it is, but in any case, here's the site where you can download it, or investigate it, or both. I figure it's worth trying. As a bonus, it works with OS X, Windows, and Linux! Hear that, nerd? Linux! Oh, and Apple's iOS... so you can get to sleep faster after finishing a game of Angry Birds between the sheets?*

the boss's kid messed up this cartoon yin-yang and the company logo was born